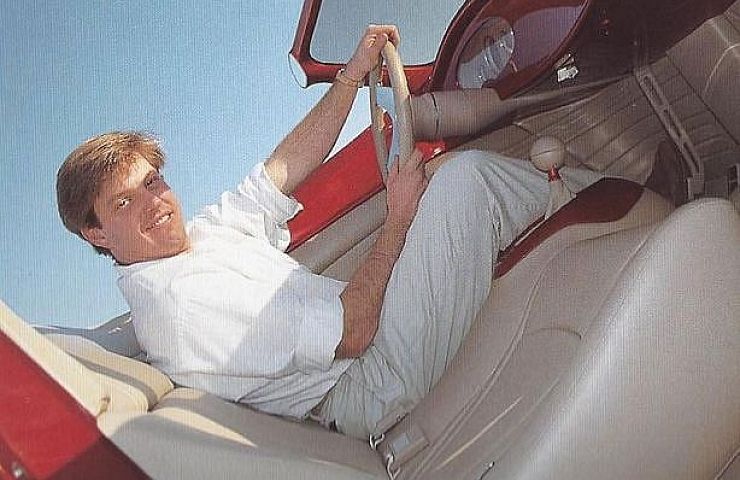

My dad Sam ran an auto body shop by day and built hot rods on nights and weekends. He started working on cars when he was 14 and on his own, working and living out of a friend’s garage where he stayed in Santa Barbara after his family moved back to Arizona. In his day, if you didn’t have the money to get help fixing your car, you learned how to do it yourself. That’s where my take-no-prisoners work ethic started.

Walking, Talking and Drawing

By the time I was three years old, I started copying my father’s drawing—anything I could get my ‘hands on.’ Sam was an accomplished and talented artist. He could draw, fabricate, weld, and do amazing body and paint. I drew and redrew his drawings over and over.

When I was 7, my daily ritual was following my dad to the shop. At the time, my dad was working for AMT/Monogram, the plastic model car company. That was the era when a boy’s introduction to car building was working on model kits. All the cool customs and race cars of the day were replicated in 1:24 scale—with chrome, customs accessories, and detailed engines. Paint came in little glass jars or small cans of candy lacquer. My dad built full-scale cars for the model company, which were used as a reference for building these kits. So, it’s only natural that I would develop an early fascination with model kits and Hot Wheels, because they represented the full-scale cars Dad and his friends worked on.

Early Lessons

I’ll never forget when my dad just finished customizing and painting a candy root-beer Lamborghini Miura. After the paint was dry, my job was to take lacquer thinner on a clean rag and wipe down any overspray that was on the rubber weather-stripping and seals. I took great care to keep any of the lacquer thinner away from the paint. When I was almost finished, my mom told me it was time for lunch. (My mom’s cooking was the only thing I loved more than cars.)

Dad continued working in the shop, saying he would catch lunch later. After quickly scarfing down the grub, I returned to the shop. It took just one glance at my dad to see that something was very wrong.

“Where did you leave the lacquer rag when you stopped for lunch?” he asked sternly.

“I left it somewhere around here,” I answered.

He raised his index finger motioning for me to follow him to the freshly painted Lambo. There, wadded up on the roof was my previously lacquer soaked rag. It had dried and was now permanently fused into the beautiful paint on the roof of the car. I learned two important lessons that day: always be accountable for your actions, and how to repair custom paint.

First Paint Job

My first paint job was a damaged hood from a 1960s VW bug—a project that would test my skills in dent repair and custom paint. I spent days massaging, hammering, and shaping the hood back to its original form, and then applied multiple layers of custom pearlescent white paint. I laid out a flame pattern in the inset panel on each side, and proceeded to mask off and apply a series of custom candy colors of various hues. After the paint dried I spent two more days color sanding and rubbing the hood to a glorious finish. It was beautiful, and I was proud of my efforts.

I carefully carried it across the shop to show my Dad and get the final inspection from the master. My dad carefully examined all my work, viewing it from various angles and running is hand over the glass-like surface. Suddenly the planishing hammer he held in his hand struck the dead center of the panel. “Now I can teach you how to fix it,” he said without emotion. That hood was the basis of almost all of the skills I learned from my dad in metal and custom paint repair, and I am eternally grateful.

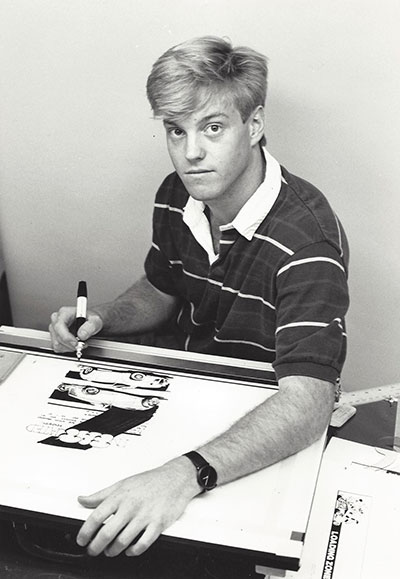

While my dad will always be my number one car-building hero, I also have to give props to Alex Tremulis. He was one of the most influential frequent visitors to my dad’s shop. Alex had a stellar career as the head designer at Auburn Duisenberg. He designed the Tucker, and managed the Ford Thunderbird Studio. Alex collaborated on projects with my father, and brought in his designs for fabrication. When I first looked at his drawings and scale models, I knew exactly I wanted to do with my life: design and build cars like Alex he did. In fact, Alex guided me and encouraged me to go to the Art Center School of Design in Pasadena. At the ripe age of 12, I knew exactly where I would attend college, and Alex wrote my recommendation later. My course was set.