Contents

Engine compression is measured in pounds per square inch (psi). The higher the engine’s compression ratio, the higher the compression psi. You can easily find the relative compression level for your specific engine online, but here’s the general rule of thumb for gas engines:

Cylinder pressure should be 15 to 20 times the compression ratio.

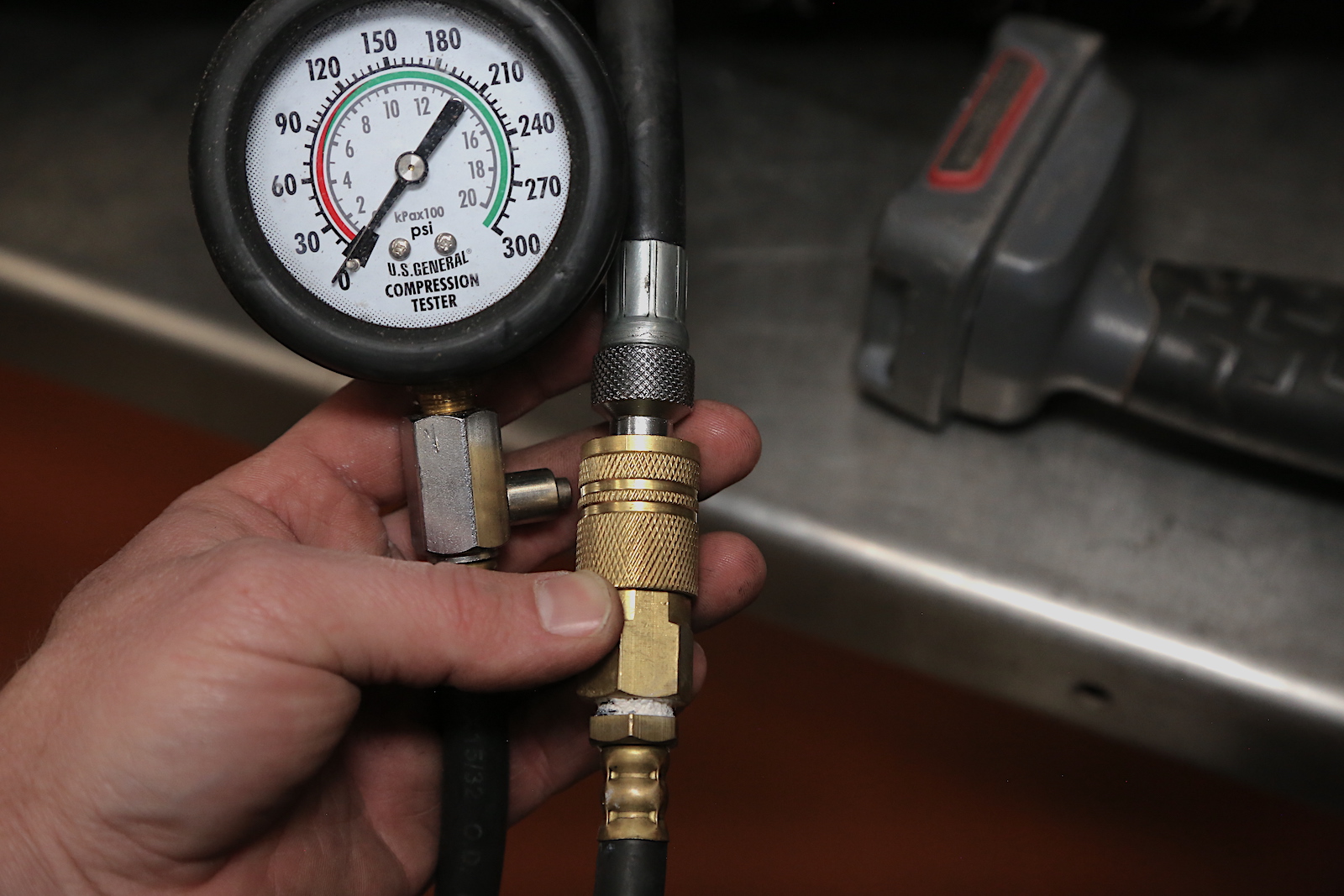

A typical compression testing gauge set with quick-connect fittings. (Photo: Jefferson Bryant)

For example, a 2014 Gen V LT1 engine has a compression ratio of 11.4:1, so the cylinder pressures should be between 170 and 228. You will find that some cylinders are a little lower and some higher, but all should fall within the 10 percent range. (This is at sea level; the pressures will reduce slightly as you go up in elevation.)

Rather than an ignition system, diesel engines use glow plugs for cold starts. They rely on compression ignition to auto-ignite the diesel mixture. The fuel is pressurized to very high levels (10,000 to 40,000 psi) to assist in the compression ignition. A diesel engine should have 275 to 500 psi of cylinder pressure.

If you are working on a diesel engine, you need a compression tool capable of reading these higher pressures. Most testers for gasoline engines go to about 300 psi, whereas gauges for diesels go to 1,000.

What Is an Engine Compression Test?

An engine compression test is part of basic engine diagnostics and can help verify a blown head gasket, a sticking or bent valve, a flat camshaft or bad lifter, or even a bad timing chain. A compression test is done through the spark plug port in each cylinder head to check the overall pressure inside the chamber.

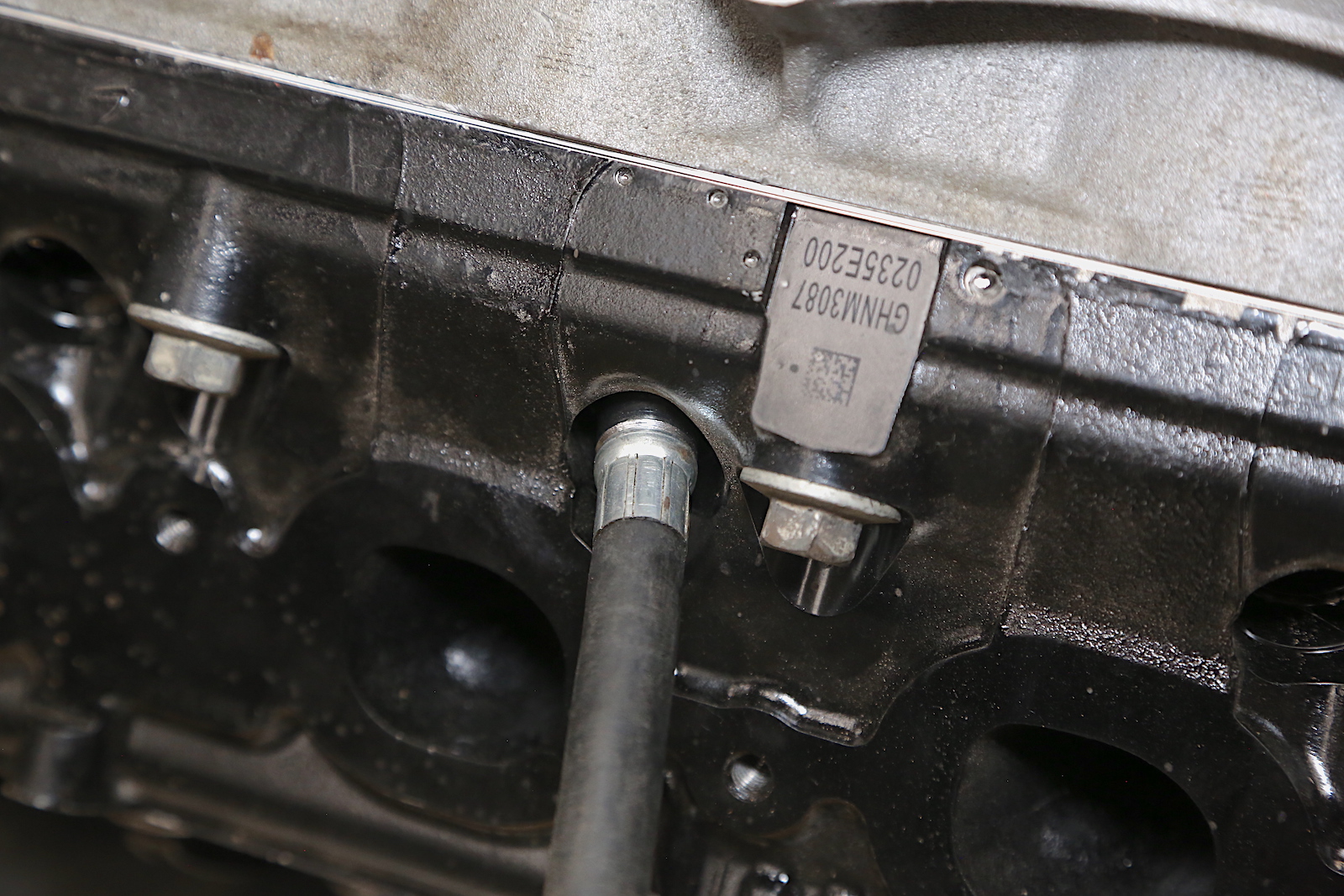

The adapter is threaded directly into the engine spark plug holes. Test each cylinder one at a time. (Photo: Jefferson Bryant)

There are two main types of compression checks: static and leak-down. Most compression gauges are for static tests since a leak-down test requires a twin-gauge tool. We’ll focus here on doing a static test.

How to Perform a Compression Test

There are several prep steps before you test the compression. You don’t want the engine to attempt to start while doing a test, as you need the starter to crank to get a good test. For modern engines, you can disable the ignition by pulling the fuse/relay for the ignition module or simply disconnect the plugs from each ignition coil.

It is also recommended that you remove the fuel pump fuse so there is no fuel in the engine. For carbureted engines, pull the ignition lead off the coil.

This kit has a quick-connect, making it easy to use in most applications. (Photo: Jefferson Bryant)

Now you’re ready to begin the engine compression testing process:

- Remove one spark plug and make a note of which cylinder it is. Some mechanics will pull every plug before doing a test to free up the engine so it cranks faster, but it’s not necessary.

- Install the adapter that matches the plug threads into the cylinder head. Some gauges have quick-connect hoses, while others use small brass adapters. If your tool is like the one shown, connect the adapter hose. If it has a brass adapter, thread it in.

- The adapter needs to seal to the head. Some engines have very deep holes for the plugs, so you may struggle to get a quick-connect style gauge adapter tight enough.

- Crank the engine using the starter. You can’t crank it fast enough by hand to get an accurate reading. The gauge should show—and maintain—the pressure until you hit the release button.

- Read the gauge and take note of the pressure.

- Press the button on the side of the gauge to release the pressure.

- Crank the engine again to verify that the pressure is the same. If not, check your fittings and gauge for seal. Retest if needed.

- The engine should rotate at least six full cycles, which means five to 10 seconds of cranking for most engines at 300 rpm. If you have an assistant, ensure they don’t do anything without your command. Body parts and tools around spinning engines are dangerous.

- Repeat this process for every cylinder, writing down each result.

Each cylinder reading should be within 10 percent of the others. If one is significantly higher or lower, you have a problem.

Problems Revealed by the Test

Several possible issues cause a loss of compression on the cylinders, depending on where the compression is lost.

For most gas engines, a 300-psi gauge is suitable. For diesel engines, 1000 psi is the norm. (Photo: Jefferson Bryant)

Single Cylinder

If one cylinder is low, you can squirt some engine oil into that combustion chamber. This will help the rings seal better and can show you if you have ring wear or another problem. If the compression jumps up to match the others, this shows ring wear. If not, then a valvetrain problem is likely to be the issue. A single cylinder with low pressure and milky oil or dark engine coolant would show a blown head gasket into a water jacket or oil port.

Two Cylinders Side by Side

If two cylinders that are next to each other both have low pressure (often close to the same psi), then there is likely a blown head gasket between the two cylinders. You may also have other symptoms, such as milky oil, dark coolant, or blue or white exhaust smoke.

All Cylinders

If every cylinder—or most of them—is lower than it should be, your valve timing is likely the cause. The valves could open and close at the wrong time, drastically reducing the cylinder pressures. Verify that the valves are moving and the timing belt or chain is spinning.

If the cylinders are low on pressure and the valves are opening correctly, the oil test described above will help the rings seal. If this addresses the issue, your engine has significant ring wear and likely needs a rebuild.

- Low compression on any cylinder is a major concern and needs to be addressed immediately.

- A blown head gasket, sticking valve, or other problem must not be ignored. It could mean the difference between a simple fix or a catastrophic failure.